“The single most memorable sound of my childhood was the clarion call of ‘Hey-y-y’ as Fearless Nadia, regal upon her horse, her hand raised defiantly in the air, rode down upon the bad guys,” acclaimed Indian playwright and director Girish Karnad wrote in 1980.

“To school kids of the mid-forties, Fearless Nadia meant courage, strength and idealism.”

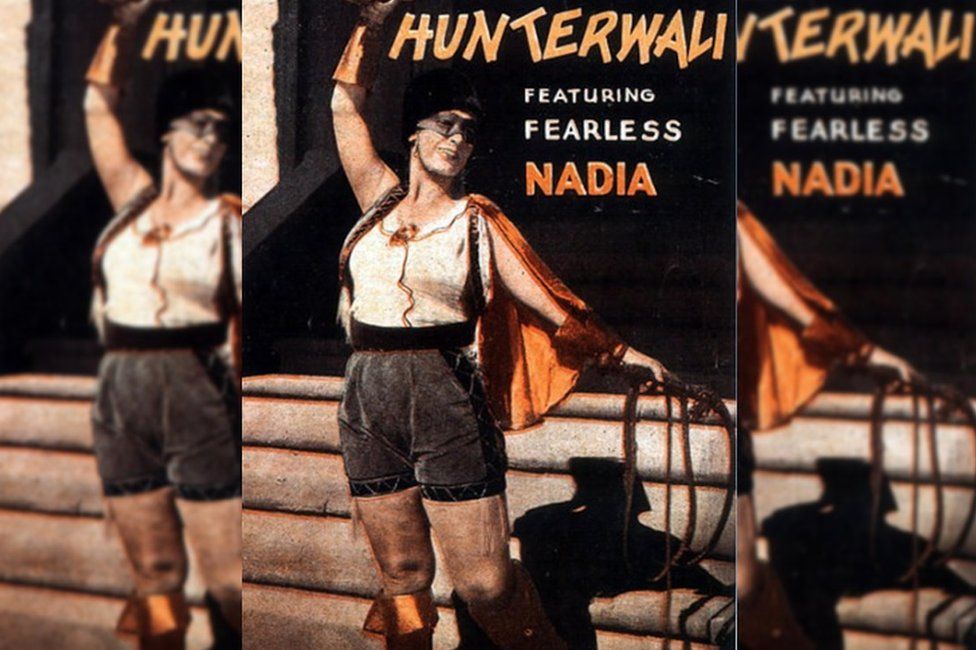

Actress and stuntwoman Mary Ann Evans, best known by her stage name Fearless Nadia, took the Indian film industry by storm in 1935 when she appeared in the Hindi film Hunterwali (The Woman with a Whip).

A blonde, blue-eyed woman of Australian origin, she made a splash as she appeared in a cape, leather shorts and knee-high boots with a whip in hand.

Evans was born in Perth, Australia, in 1908 to a Greek mother and British father, according to Rosie Thomas, author of Bombay before Bollywood. She arrived in India in 1911 with her father’s army unit but settled with her family in Bombay (now Mumbai) after his death.

According to Thomas, Evans – who’d grown up learning dance and horse-riding – toured India with a Russian ballet troupe and briefly performed for a circus.

The young performer became known as a singer and dancer, performing at all kinds of venues across the country.

She was working in theatre and circus in the early 1930s when she was discovered by prominent Bollywood movie director JBH Wadia.

Wadia initially cast her in small roles in films produced by his studio Wadia Movietone, which he ran with his brother Homi.

Evans was great at stunts and had a “can-do-anything attitude”, says Roy Wadia, JBH Wadia’s grandson.

So the Wadia brothers cast her in her first lead role in Hunterwali, in which she played an avenging princess who turns into a masked vigilante as she seeks revenge for her father’s death at the hands of an evil court official.

But while they were thrilled with their new star, others were not quite as ready to embrace their vision.

“The financiers of the film were quite horrified that these Parsi brothers would star a blonde, blue-eyed, white woman in a film where she was wearing hot pants and leather vests and carrying a whip and basically beating up all these bad guys in the film,” Roy Wadia says.

So they pulled out and the Wadia brothers released the film themselves.

The 1935 film was a huge hit, running houseful in theatres for weeks, and Evans went on to become the top box-office female star of the 1930s and 1940s, according to Thomas.

The film’s success also transformed Wadia Movietone into a studio known for films with fantastic stunts and theatrics. Evan’s famous yell “hey-y-y” in Hunterwali became a catchphrase.

“The roles she played, and the screenplays that my grandfather created for her, were about emancipation, about the freedom struggle, about literacy, about anti-corruption – all themes that were particularly relevant at that time of huge social change and turmoil [of the Indian Independence movement],” says Roy Wadia.

“Although strict British censorship forbade overt references to the freedom movement, film-makers of the 1930s and 1940s would slip casual references to Congress [party] songs and symbols into the soundtrack or screen,” Thomas writes.

“Nadia saw her role – on-screen and off – as supporting the nationalist movement and stated explicitly, ‘In all the pictures there was a propaganda message, something to fight for, for example for people to educate themselves or to become a strong nation’.”

Her roles often featured her as a cosmopolitan woman who took charge to physically fight off villains in her films, often flipping burly men over her shoulder.

“She would be jumping off waterfalls, jumping off planes, riding horses bareback, swinging on chandeliers, jumping 30ft from the roof of a castle – all stunts she did herself,” Roy Wadia says.

“In those days, there were no safety nets, no body doubles and certainly no stamped insurance.”

The actor’s dynamism and skill at stunts helped sell her on-screen persona to a fascinated audience. But they were not always an easy feat.

In a 1980 interview with Karnad, Evans talked about one of her most terrifying moments from a film shoot. The actor was working on Jungle Princess (1942), which had a scene with a lion.

“We started shooting and suddenly a lioness called Sundari gave an enormous roar and jumped. She jumped straight across my head, Homi’s head, the photographer’s head and barged through the cage, and there she was, hanging with her head and front paws on the outside and the rest of her inside.”

The lion trainer eventually got her out unharmed.

In her films, Evans often switched easily from Western clothing to Indian attire. “Always with a sense of humour and glint in the eye that lets you know that she’s like a chameleon but not really changing because under all that she remains the same person,” Roy Wadia says.

Evans eventually fell in love and became Homi Wadia’s partner, a relationship that was not approved by many in the Wadia family. The couple had the staunch support of his brother JBH Wadia, but they only married after Wadia’s mother passed away.

Roy Wadia remembers Evans as a down-to-earth, ordinary woman with a great sense of humour. “She had this huge laugh, she would make all sorts of jokes – naughty ones as well.”

Every year Evans and Homi Wadia would throw a Christmas party at their shack in Juhu, where they entertained everyone from industry colleagues, family members to friends.

“Homi would dress up as Santa Claus and make his appearance in all sorts of dramatic ways. And Mary was his partner in crime there,” Roy Wadia recalls.

The couple did not have children, but Homi Wadia adopted Evans’s son from a previous relationship. Evans died in 1996 soon after her 88th birthday. She was perhaps the first foreigner to attain cult status in Bollywood.