Culinary legend Madhur Jaffrey celebrates the 50th anniversary of her seminal book, An Invitation to Indian Cooking, which put Indian food on tables around the world.A

At a spirited 90 years of age, Madhur Jaffrey takes centre stage on the streaming platform MasterClass, her screen presence marked by a shiny bob, smoky-lined eyes, vivid red lips and a trove of lively, endearing anecdotes from her rich life. A true polymath, Madhur is more than a versatile actress whose cinematic impact has spanned several decades, she’s a culinary chronicler and food icon. With over 30 cookbooks to her name, spanning the flavours of India, Asia and global vegetarian cuisine, as well as many television cookery shows (including on the BBC), Madhur Jaffrey is a household name for anyone with a taste for South Asian cuisine.

As Indian-born Nobel Laureate and cookbook author Abhijit Banerjee shared during this year’s annual HC Mahindra Lecture at Harvard University, “While I could cook many Western dishes, I did not know how to cook Indian food. My first step was smart – to buy her [cookbook], An Invitation to Indian Cooking, and follow it with a certain amount of diligence. And that’s how I learned to cook Indian food.”

GLOBAL CHEF CHAMPION

For over half a century, Madhur Jaffrey has taught countless people about Indian cooking, expertly crafting and documenting Indian traditions and recipes in myriad books and on television.

The 50th anniversary edition of Jaffrey’s ground-breaking book comes out on 21 November, beautifully illustrated with Jaffrey’s drawings and a foreword by chef and fellow cookbook author Yotam Ottolenghi.

“It’s amazing how prescient the title of the book was for the arc of Jaffrey’s writing career,” said Matt Sartwell of the legendary New York City food bookstore Kitchen Arts and Letters. “When An Invitation to Indian Cooking first came out in 1973 in the US, cooking Indian food was challenging for many people, as the availability of ingredients was highly erratic. Fifty years ago, people didn’t think casually about mail ordering from a vendor in some other part of the country,” he recalled.

Born in 1933, in pre-Partition India, Jaffrey was the youngest of six children in an affluent Delhi-based family. Her histrionic talents took her to London, where she studied at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and worked in the city’s theatre scene. She married fellow Indian dramatist Saeed Jaffrey, with whom she migrated to America in 1958. While she swiftly rose to fame as a film actress, notably in Merchant-Ivory productions, Jaffrey’s journey in New York City took a different turn after parting ways with Saeed in 1966.

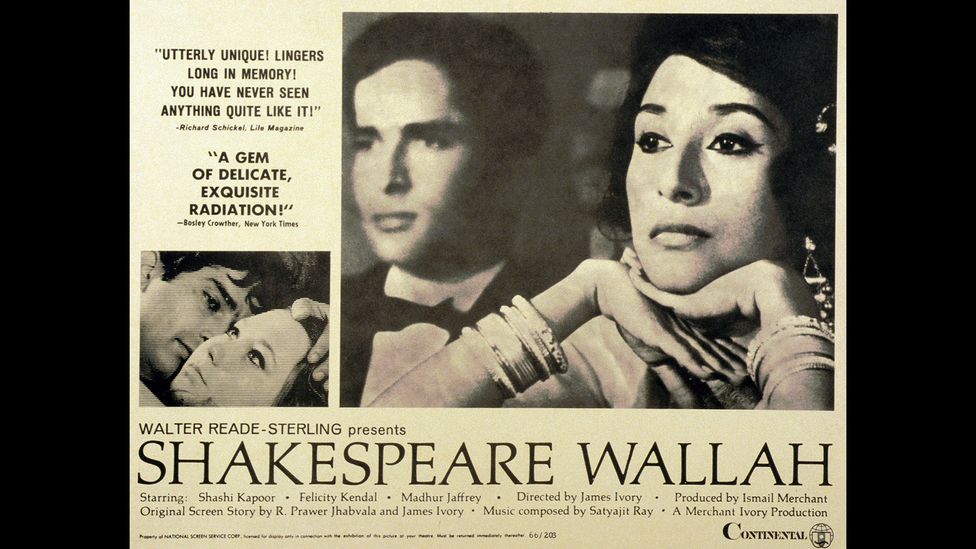

Navigating the complexities of solo parenthood with three children, Jaffrey found solace and purpose in her culinary prowess, cooking and entertaining frequently at home. After winning an award for her work in a film called Shakespeare Wallah, she was approached by The New York Times food critic, Craig Claiborne for an interview. This fortuitous meeting gave Jaffrey an unforeseen visibility, a windfall she astutely decided to channel into the creation of a cookbook.

As recounted by legendary book editor, Judith Jones, in her memoir, The Tenth Muse: My Life in Food, Jaffrey’s manuscript was extremely compelling. Jones wrote, “When Madhur Jaffrey’s manuscript came to me at Knopf, I was immediately persuaded that food-conscious Americans were ready for authentic Indian cuisine, particularly if they had someone as skilful as Madhur guiding them. She was canny enough to realise, it was apparent, that she had to seduce us slowly, step by step.”

Jaffrey seamlessly transitioned into a cultural ambassador, expertly crafting and documenting Indian traditions and recipes for an intrigued American audience. Jaffrey explained that when she started writing about Indian food, she felt people knew so little about it. “In the global culinary arena, Indian cuisine often grapples with misconceptions and preconceived notions. Outsiders frequently blur the lines between spice and heat, a balance shaped by regional influences and contexts. Indian eateries abroad, unfortunately, perpetuated stereotypes by predominantly offering nationalistic dishes, while much of the food writing contributed to an air of mystique, rather than demystifying Indian flavours,” she said.

“They always called it ‘curry’, and one curry powder went into everything, making it all taste the same,” Jaffrey added. “I used to tell them we have such varied food in India. I feel if they know a little more about the variety within India and our exquisite dishes and ingredients – and trust me, even Indians don’t know that – that would be great!”

“I think Madhur had a vision of where she wanted to take people,” said Sartwell, “and she has stayed true to that, keeping her point of view, and these days, when you can get all the recipes you want for free, what people still tend to pay for is a point of view. And she offers people rewards for that.

In 2022, Jaffrey was awarded one of India’s highest civilian honours, the Padma Bhushan, for her cultural ambassadorship through cuisine. Indian journalist Vikram Doctor recounted how people would thank her for helping them learn how to cook through her clearly written and comprehensive recipes.

Madhur Jaffrey won an award for her work in a film called Shakespeare Wallah (Credit: LMPC/Getty Images)

“I once saw how she got those recipes”, he said excitedly. “During a visit to [the restaurant] Highway Gomantak, Madhur wanted to learn how to make the rice bhakri [round flatbreads] she was served, from the owners, the Potnis family. Madhur listened keenly as Mrs. Potnis concluded the steps involved, and remarked, ‘Something is missing! Madhur persisted, and Mrs. Potnis finally remembered one detail. Just before you put the bhakri on the hot tawa [frying pan or griddle], sprinkle some water. And indeed, that steam prevents the bhakri from sticking. It was a masterclass in how to get an Indian recipe.”

Jaffrey herself reiterates her hunger for this sort of tacit knowledge. “There is nothing like traveling to the country, cooking with people in their homes, feeling the emotions as you sit down and eat the food together with the family. You see the hands moving, and how they are picking up the food, and there is an emotional content in all of that that makes the food so valuable.”

“Everyone can cook from a good cookbook,” she added. “I always try to eat at people’s homes in India. I watch them cook, observe the heat, whether they are stirring it lazily or doing it swiftly, and write all these things for my readers. But if I don’t watch someone make it, then what have I learned?”

Through much of this experience of tasting her way through her travels, Jaffrey had a steadfast accomplice in her second husband, classical musician Sanford Allen, who has done more than just help her with the technical parts of writing a book. “Emotionally, Sanford has always been there, tasting all the food and encouraging me to write. He has always complained that I make one thing and never make it again; it disappears. He sometimes stands behind me and writes it down. I tell him, ‘It’s what’s in the fridge, and I just put it together for dinner!’ He has preserved recipes I would not have preserved.”

Madhur Jaffrey crafted Indian recipes for a Western audience (Credit: Trinity Mirror/Mirrorpix/Alamy)

In the landscape of writing about the food culture of India, Jaffrey certainly has her own unique style. “Madhur did something else, which other Indian culinary luminaries did not do. In An Invitation to Indian Cooking, she introduced the reader to the food in its context,” said Doctor. While the book does not have many autobiographical details, it abounds with cultural context and evocative food memories that nourished her childhood. Jaffrey’s prowess for storytelling is apparent in the book’s introduction as she scripts how curry powder could have been the imaginative recreation of a home-bound British officer (she suggests David Niven). Her writing has an aural quality, putting the reader in the place of action – the home kitchen.

Jaffrey’s steady, guiding voice provides a sense of being in safe hands. With decades of observing cookbook customers, Sartwell said, “Madhur is famous for being consistent and trustworthy, and she can put herself in a cook’s head and anticipate questions they might ask about the process, which speaks to a certain intellectual and emotional sympathy. And as she extends that hand, you feel the presence of someone who will treat you well once you have taken it.”

Fellow author Claudia Roden came to fame alongside Jaffrey, when Judith Jones published her seminal book, A Book of Middle Eastern Food, side-by-side with An Invitation to Indian Cooking. Since meeting at a party in James Beard‘s home in New York City, Roden and Jaffrey have been friends for over half a century, sharing culinary trips and annual encounters at the Oxford Food Symposium back in the UK. “Madhur drew the map on what was – and always is – valuable in food culture,” said Roden. “All the new culinary innovations are marvellous. But she felt at the time she had to record a tradition. And she has a very refined palette, so she succeeds in keeping the soul and essence of these recipes.”

Madhur Jaffrey has appeared in many television cookery shows over the years (Credit: Cinematic/Alamy)

While there have been many editions of An Invitation to Indian Cooking published through the decades, there have been few revisions. Jaffrey explained: “Everything is sort of the same. People know about Indian food, and they don’t know about Indian food. They pick up odd parts of it, like turmeric, or tamarind… But not the wholeness of Indian food … Indian food is not one ingredient or two ingredients. It’s the combination! The magical combination of the ingredients in every dish makes Indian food.”

“Indian food is not one ingredient or two ingredients. It’s the combination! The magical combination of the ingredients in every dish makes Indian food.”

When it comes to the future of Indian food, Jaffrey is passionate about what to share with the world. “I wish Indian chefs would tell us the stories they discover. What makes them feel that this dish is wonderful? I just want to know what you love and why you love it,” she said.

But Jaffrey has a request for others discovering the plethora of ingredients and techniques from India. “I do not want them to muddle up too many things in a dish. There is kimchi in it, a little from Thailand or something from India or Vietnam, like a flitting butterfly,” she said. “A little bit of this, a little bit of that, it doesn’t do anything for me. I want food to be emotional. And for it to be emotional, you want it to be with you for some time. It has to develop within you, your family and your society to have any emotion or meaning.”

Madhur Jaffrey’s cauliflower with onion and tomato dish (Credit: Priya Mani)

Cauliflower with onion and tomato recipe

By Madhur Jaffrey

Serves 6-8

“When I delved into the nuances of cauliflower, I discovered its Western origins in India,” said Jaffrey. “Despite its absence from our festive feasts, cauliflower has graced our family table since my early childhood. My mother would concoct a dish with cauliflower and grate a can of Kraft’s cheddar cheese, a distinctly Western touch amid masalas and all, making it her own. I cherished every incarnation of cauliflower; it’s been a constant in my life from the beginning.”

INGREDIENTS

1 medium- sized onion, peeled and coarsely chopped

4 cloves garlic, peeled and coarsely chopped

a piece of fresh ginger, 5cm long and 2½cm wide (2-by-1in), peeled and coarsely chopped

1 large head fresh cauliflower, or 2 small ones

8 tablespoons vegetable oil

½ tsp ground turmeric

1 medium-sized fresh or canned tomato, peeled and chopped

1 tbsp chopped coriander

1 fresh hot green chilli, washed and finely sliced, or ¼ tsp cayenne pepper (optional)

2 tsp ground coriander

1 tsp ground cumin

1 tsp garam masala

2 tsp salt

1 tbsp lemon juice

Method

Step 1

Put the chopped onion, garlic and ginger in a blender with 4 tbsp of water and blend to a paste.

Step 2

Break off the cauliflower into small florets, not longer than 2½-4cm (1-1½in), and not wider at the head than 1-2½ cm (½-1in). Wash in a colander and leave to drain.

Step 3

Heat the oil in a heavy-bottomed 25-30cm (10-12in) pot over a medium flame, pour in the paste from the blender and add the turmeric. Fry, stirring, for 5 minutes.

Step 4

Add the chopped tomato, chopped coriander and green chilli or cayenne and fry 5 minutes. If necessary, add 1 tsp of warm water at a time and stir to prevent sticking. Now put in the cauliflower, ground coriander, cumin, garam masala, salt and lemon juice. Stir for a minute. Add 4 tbsp warm water, stir, cover, lower flame and allow to cook slowly 35 to 45 minutes (the tightly packed cauliflower heads take longer to cook). Stir gently every 10 minutes or so. The cauliflower is done when each floret is tender with just a faint trace of crispness along its inner spine.

Step 5

To serve, lift out gently and place in a serving dish – a low, wide bowl would be best. Serve with hot chapatis [griddle-cooked flatbreads], pooris [fried breads] or parathas [flaky flatbreads] or serve with any kind of lentils and plain boiled rice.