Last month, India made history when it became the first country to land a lunar mission near the Moon’s south pole.

Chandrayaan-3’s lander and rover – called Vikram and Pragyaan – spent about 10 days in the region, gathering data and images to be sent back to Earth for analysis.

Earlier this month, scientists put them to bed as the Sun began to set on the Moon – to be able to function, the lander-rover need sunlight to charge their batteries. The country’s space research agency Isro said it hoped that they would reawaken “around 22 September” when the next lunar day breaks.

Isro has provided regular updates on their movements and findings and shared images taken by them.

These updates have excited many Indians, but others have been asking about the significance of these discoveries.

The BBC asked Mila Mitra, a former Nasa scientist and co-founder of Stem and Space, a Delhi-based space education company, to pick some of Chandrayaan-3’s major findings and explain their significance.

The distance covered – and craters avoided

Hours before the rover was put to bed on 2 September, Isro said Pragyaan “has traversed over 100m [328 feet] and is continuing”.

That’s quite a long way to travel for the six-wheeled rover, which moves at a speed of 1cm per second.

What is also significant, Ms Mitra says, is that it has been able to stay safe and avoid falling into the craters that dot the Moon’s little-explored south pole region.

The rover, she says, has a special wheel mechanism – called rocker bogie – which means that all its wheels don’t move together, helping it traverse up and down, but it may not be able to climb out if it falls into a deep crater. So it’s important to make it go around the craters or even retrace its steps. And that, Ms Mitra adds, is done by scientists at the command centre who are “watching the Moon through the rover’s eyes”.

“The rover is not automated and its movements are controlled from the command centre which acts on the basis of the pictures it sends.

“There’s a slight delay before they reach the command centre because of the circuitous route they take – Pragyaan sends them over to the lander which sends them on to the orbiter to pass them on to Earth.”

So, by the time the command reaches the rover, it’s a few steps closer to the threat.

But the fact that it has managed to navigate safely around two craters shows that it’s able to communicate really quickly with the command centre, Ms Mitra adds.

Blowing hot and cold

The first set of data collected from the lunar topsoil and up to the depth of 10cm (4 inches) below the surface from a probe onboard the Vikram lander showed a sharp difference in temperatures just above and below the surface.

While the temperature on the surface was nearly 60C, it plummeted sharply below the surface, dropping to -10C at 80mm (around 3 inches) below the ground.

The Moon is known for extreme temperatures – according to Nasa, daytime temperatures near the lunar equator reach a boiling 120C (250F), while night temperatures can plunge to -130C (-208F). And temperatures of -250C (-410F) have been recorded at craters which never receive any sunshine and remain permanently in shadows.

But, Ms Mitra says, this wide variation in temperature is significant because it shows that Moon’s soil – called lunar regolith – is a very good insulator.

“This could mean it could be used to build space colonies to keep heat and cold and radiation out. This would make it a natural insulator for habitat,” she says.

It could also be an indicator of the presence of water ice below the surface.

A clue into the Moon’s evolution

When a laser detector mounted on the rover measured the chemicals present on the lunar surface near the south pole, it found a host of chemicals such as aluminium, calcium, iron, chromium, titanium, manganese, silicon and oxygen.

But the most important of the findings, scientists say, relate to sulphur. The instrument’s “first-ever in-situ – in the original space” measurement “unambiguously confirms” the presence of sulphur, Isro said.

Sulphur’s presence on the Moon has been known from the 1970s, but scientists say the fact that the rover has measured sulphur on the lunar surface itself – and not inside a mineral or as part of a crystal – makes it “a tremendous accomplishment”.

Ms Mitra says the presence of sulphur in the soil is significant on a number of counts.

“Sulphur comes usually from volcanoes so this will add to our knowledge of how the Moon was formed, how it evolved and its geography.

“It also indicates the presence of water ice on the lunar surface and since sulphur is a good fertiliser, it’s good news as it can help grow plants if there’s habitat on the Moon.”

Was it really a Moonquake?

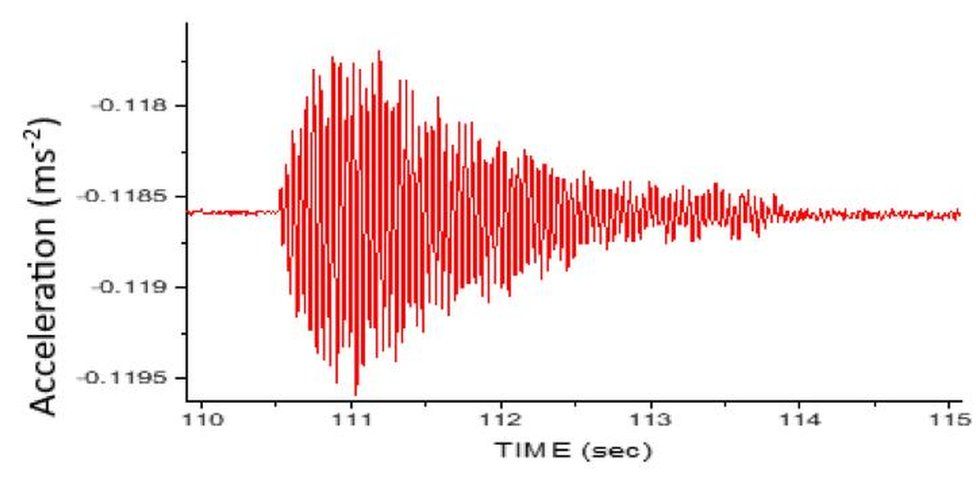

The Vikram lander carries an instrument that measures vibrations emanating from its own studies and experiments as well as those from the rover and its activities.

Isro said while the Instrument for Lunar Seismic Activity (Ilsa) had its ear to the ground, it also recorded “an event, appearing to be a natural one” and was investigating its source.

This event had much larger amplitude which means it was much stronger, Ms Mitra says, adding that there could be several explanations for this.

“It could be some space debris – such as a meteorite or an asteroid – hitting the surface. Or it could be seismic which would make it the first Moonquake recorded since the 1970s. In that case, this could lead to an explanation of what’s under the Moon’s surface and its geography.”

What’s lunar plasma?

When Isro posted on X (formerly Twitter) that a probe on the lander had done the “first-ever measurements of the near-surface lunar plasma environment” of the south polar region and found it to be “relatively sparse”, many wondered what it meant.

Ms Mitra explains that plasma refers to the presence of charged particles in the atmosphere which could hinder the radio-wave communication that Chandrayaan-3 is using.

“The fact that it’s very sparse or thin is good news as it means it will disrupt the radio communication a lot less.”

When the lander hopped

The last thing the Vikram lander did before being put to bed in early September was what Isro called a “hop experiment”.

The agency said the lander was “commanded to fire its engines, it rose up by about 40cm [16 inches] and landed at a distance of 30-40cm”.

This “successful experiment” means the spacecraft could be used in future to bring samples back to the Earth or for human missions, it added.

Now, could this short hop mean a giant leap for India’s future space plans?

Ms Mitra says the “hop tested restarting the engine after a lunar landing to make sure it is still operating fine”.

It also demonstrated that the craft has the “capacity for lift-off in a lunar soil environment since so far the testing and real lift-off has only been from Earth”, she adds.

Source: BBC